Embodied Visions:

Interactive Installations That Reimagine Bodily Presence

in Digital Imaging Apparatuses as Shadows

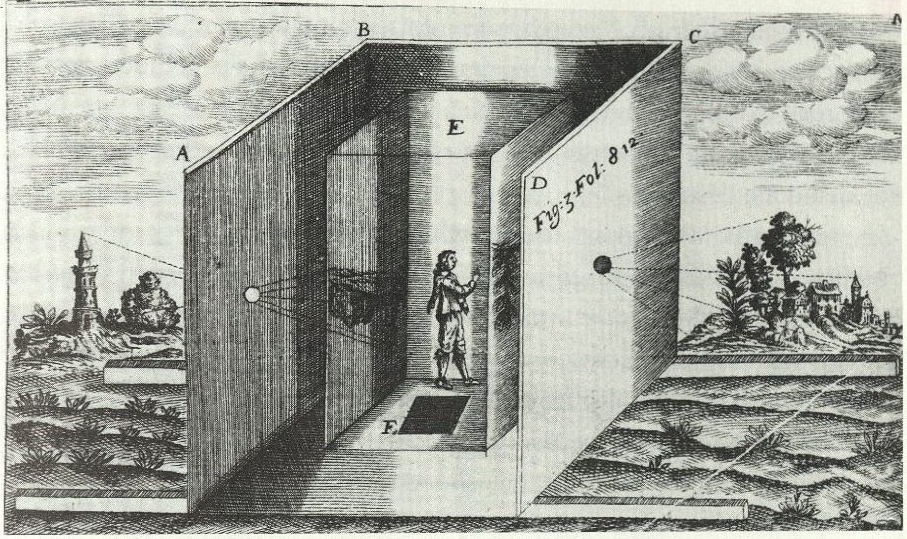

From pinhole cameras to DSLR and VR, imaging and display technologies have played important roles in shaping visual reality. The evolution of imaging devices is accompanied by the abstraction of spatial relationships between the body of the observer, the apparatus, and physical reality. In his book Techniques of the Observer1, art historian Jonathan Crary performs a media archaeological study of imaging models from the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries. According to Crary, the body of the observer was an integral part of early imaging devices like the pinhole camera, and the development of stereoscopes in the nineteenth century moved the site of visualizing reality from screens to right before the eyes of the observer. Consequently, the body and subjectivity were further abstracted from the imaging model and the reality being visualized.

Crary’s arguments can be extended into the 21st century, where VR and digital photography largely abolish the spatial model and bodily presence in imaging. Although emerging technologies and their epistemological implications are extensively studied in cultural studies, state-of-the-art imaging devices tend to portray human subjects as passive users instead of active observers. While embracing technological innovations, is it possible to preserve an imaging system today where the observer’s bodily presence remains relevant?

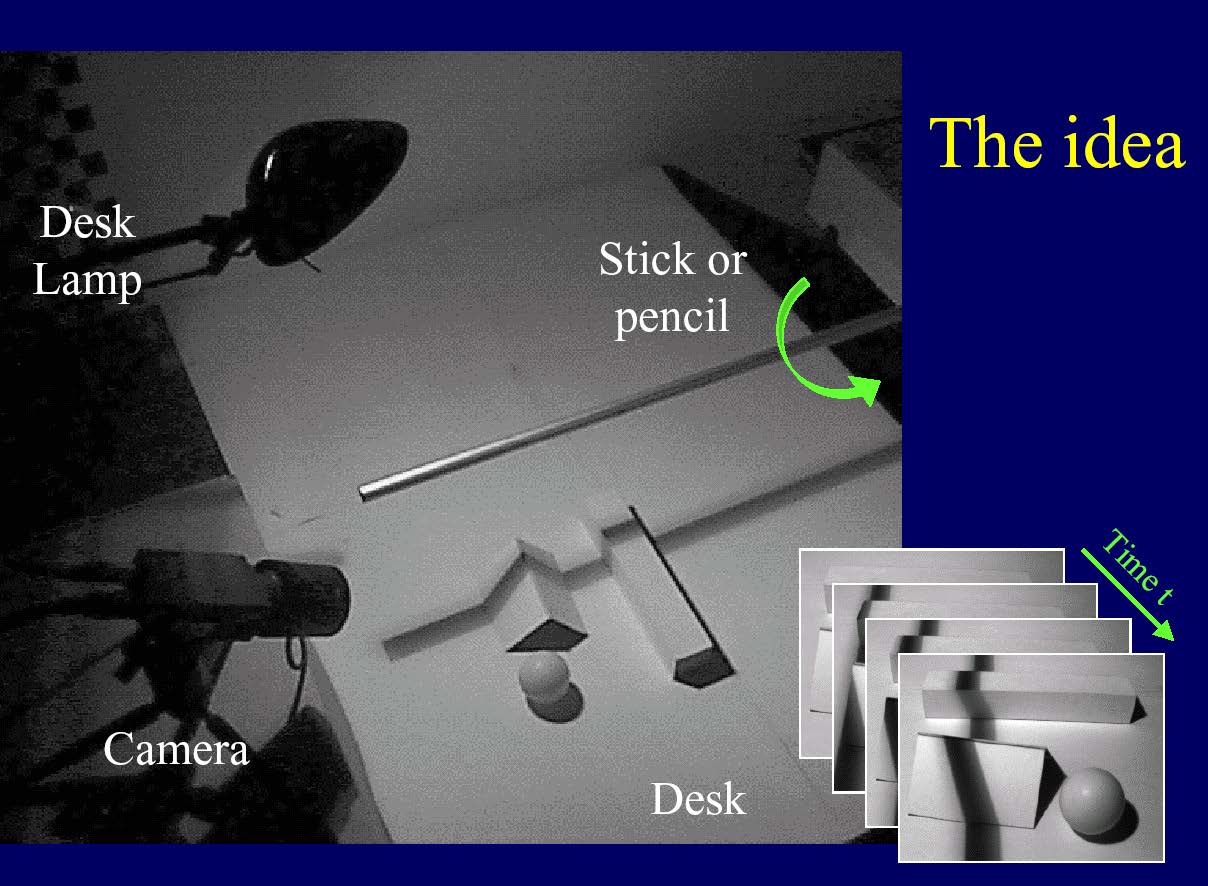

In response, Embodied Visions revisit the hardware and algorithmic infrastructure of digital imaging seeking to integrate bodily presence. From Western media archaeology, we were inspired by the story of Dibutades, the Corinthian maid who traced her lover’s shadow before his departure to keep her company. The story shows that since ancient times, shadows have been used in imaging as a double and a visual proxy of the body. Since then, shadows and projectors have been widely adopted by artists including Olafur Eliasson, Rafael Lozano-Hemmer and Rosa Barba to animate the relationships between the bodies of the observers and physical space. They are also key components in state-of-the-art imaging technologies, including structural lighting2 and dual photography3. To form live shadows, we leverage the projectors’ capability of displaying both the digital image transmitted as digital signals and the optical image formed along the path of light transmission.

Using shadows as the main motif, the three installations form a narrative that progressively contends with the limitations of existing digital imaging models and proposes alternatives where bodies actively interact withimaging pipelines, physical space, and other subjects. wearing you lets shadows go rogue by inconspicuously replacing one’s silhouette with someone else’s recording, highlighting the simulated and disembodying nature of digital imaging. penumbra dance reveals images inside shadows and challenges the mutual exclusion between (digital) images and (optical) shadows. we’ll meet where there is no shadow allows participants to connect without verbal communication by inhabiting each other’s bodies; matching the pose of the other participant reveals the other side of the wall, turning the physical partition transparent and establishing intimacy through visual and bodily copresence. Together, "Embodied Visions" respond to the disembodying nature of digital imaging by exposing its ambiguities and interactive potentials. It proposes embodied alternatives that unify the optical and the digital, and the dystopian and the spectacle.

1 Jonathan Crary. 1990. Techniques of the observer: on vision and modernity in the nineteenth century.MIT Press., MIT Press.

2 Jean-Yves Bouguet and Pietro Perona. 1999. 3D Photography Using Shadows in Dual-Space Geometry. International Journal of Computer Vision 35, 2 (Nov. 1999), 129–149.

3 Pradeep Sen, Billy Chen, Gaurav Garg, Stephen R. Marschner, Mark Horowitz, Marc Levoy, and Hendrik P. A. Lensch. 2005. Dual photography. ACM Transactions on Graphics 24, 3 (July 2005), 745–755.

Crary’s arguments can be extended into the 21st century, where VR and digital photography largely abolish the spatial model and bodily presence in imaging. Although emerging technologies and their epistemological implications are extensively studied in cultural studies, state-of-the-art imaging devices tend to portray human subjects as passive users instead of active observers. While embracing technological innovations, is it possible to preserve an imaging system today where the observer’s bodily presence remains relevant?

In response, Embodied Visions revisit the hardware and algorithmic infrastructure of digital imaging seeking to integrate bodily presence. From Western media archaeology, we were inspired by the story of Dibutades, the Corinthian maid who traced her lover’s shadow before his departure to keep her company. The story shows that since ancient times, shadows have been used in imaging as a double and a visual proxy of the body. Since then, shadows and projectors have been widely adopted by artists including Olafur Eliasson, Rafael Lozano-Hemmer and Rosa Barba to animate the relationships between the bodies of the observers and physical space. They are also key components in state-of-the-art imaging technologies, including structural lighting2 and dual photography3. To form live shadows, we leverage the projectors’ capability of displaying both the digital image transmitted as digital signals and the optical image formed along the path of light transmission.

Using shadows as the main motif, the three installations form a narrative that progressively contends with the limitations of existing digital imaging models and proposes alternatives where bodies actively interact withimaging pipelines, physical space, and other subjects. wearing you lets shadows go rogue by inconspicuously replacing one’s silhouette with someone else’s recording, highlighting the simulated and disembodying nature of digital imaging. penumbra dance reveals images inside shadows and challenges the mutual exclusion between (digital) images and (optical) shadows. we’ll meet where there is no shadow allows participants to connect without verbal communication by inhabiting each other’s bodies; matching the pose of the other participant reveals the other side of the wall, turning the physical partition transparent and establishing intimacy through visual and bodily copresence. Together, "Embodied Visions" respond to the disembodying nature of digital imaging by exposing its ambiguities and interactive potentials. It proposes embodied alternatives that unify the optical and the digital, and the dystopian and the spectacle.

1 Jonathan Crary. 1990. Techniques of the observer: on vision and modernity in the nineteenth century.MIT Press., MIT Press.

2 Jean-Yves Bouguet and Pietro Perona. 1999. 3D Photography Using Shadows in Dual-Space Geometry. International Journal of Computer Vision 35, 2 (Nov. 1999), 129–149.

3 Pradeep Sen, Billy Chen, Gaurav Garg, Stephen R. Marschner, Mark Horowitz, Marc Levoy, and Hendrik P. A. Lensch. 2005. Dual photography. ACM Transactions on Graphics 24, 3 (July 2005), 745–755.

wearing you, interactive installation, 2024

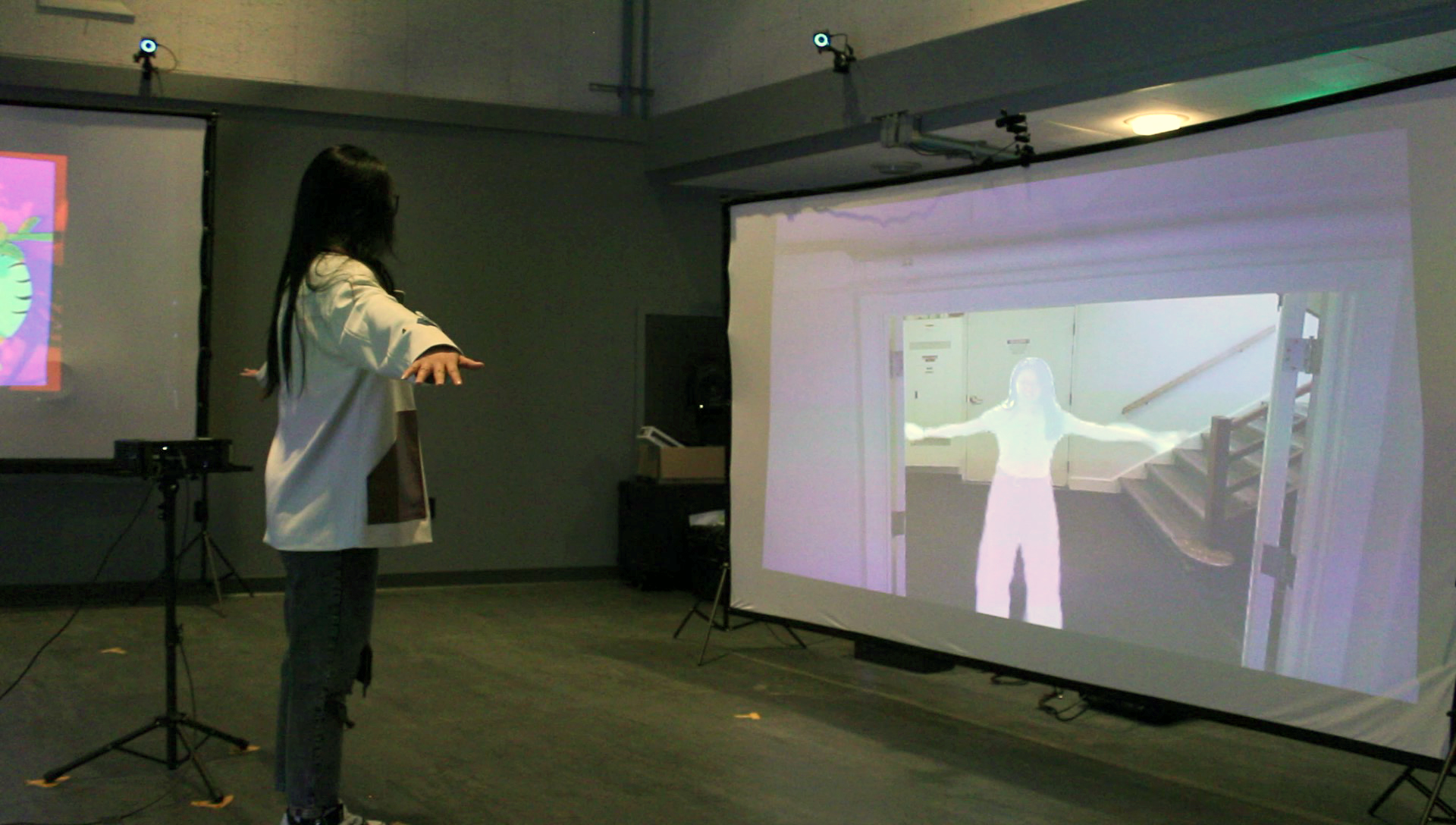

This installation highlights the simulated and disembodying nature of conventional digital imaging. By inconspicuously replacing optical shadows with computed ones, it challenges the assumption that shadows always copy our gestures. The participant first sees a projection of his or her silhouette segmented from a webcam livestream. For a few seconds, the shadow moves exactly as the body. Then, the algorithm starts matching the participants’ poses against existing ones from a database of video recordings of previous visitors. As soon as a match is found, the projected live stream is smoothly replaced by the recorded clip indexed by the pose, leaving the participant baffled when the shadow stops following his or her movement and becomes someone else’s.

This installation highlights the simulated and disembodying nature of conventional digital imaging. By inconspicuously replacing optical shadows with computed ones, it challenges the assumption that shadows always copy our gestures. The participant first sees a projection of his or her silhouette segmented from a webcam livestream. For a few seconds, the shadow moves exactly as the body. Then, the algorithm starts matching the participants’ poses against existing ones from a database of video recordings of previous visitors. As soon as a match is found, the projected live stream is smoothly replaced by the recorded clip indexed by the pose, leaving the participant baffled when the shadow stops following his or her movement and becomes someone else’s.

penumbra dance, interactive installation, 2024

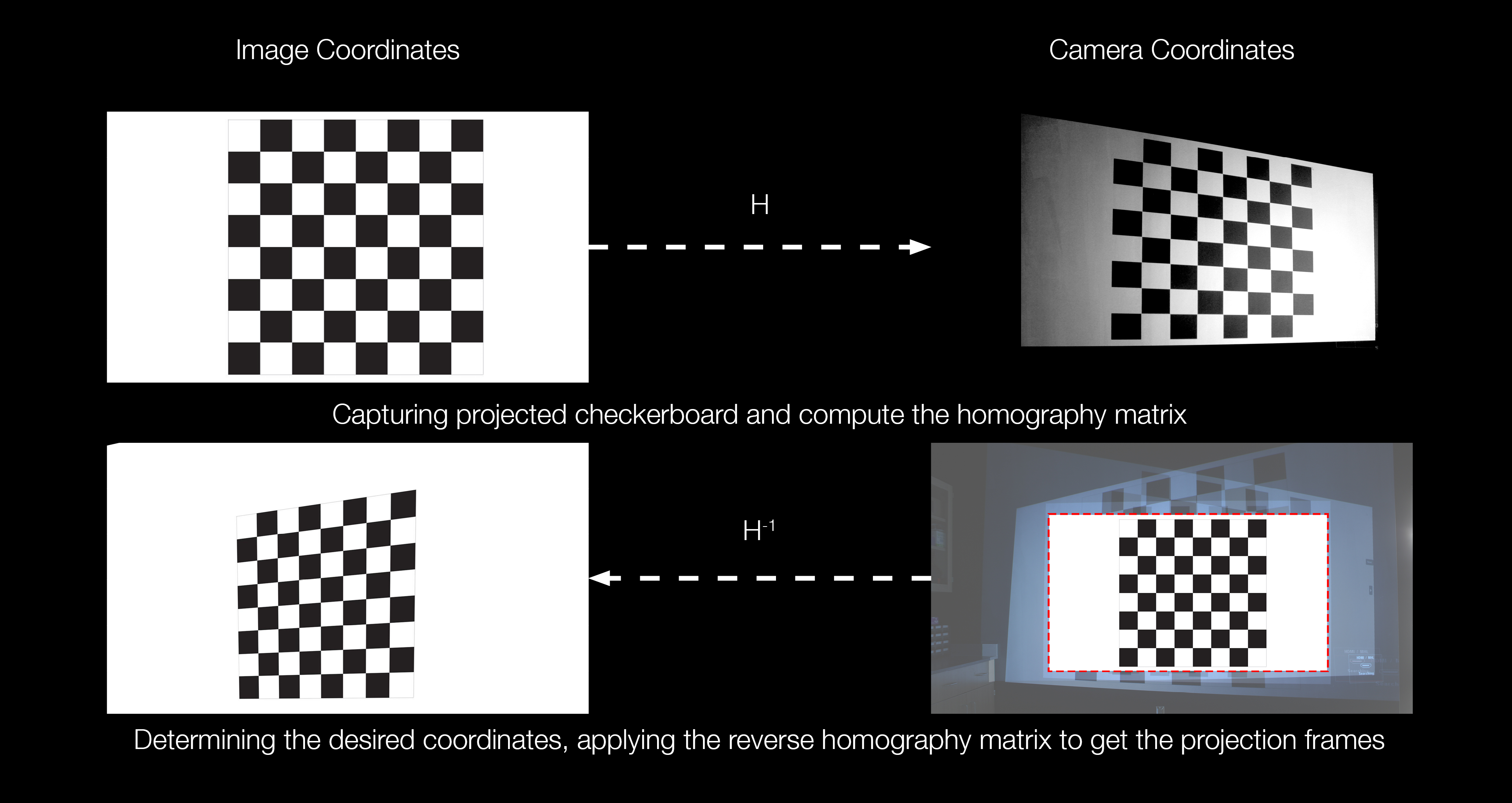

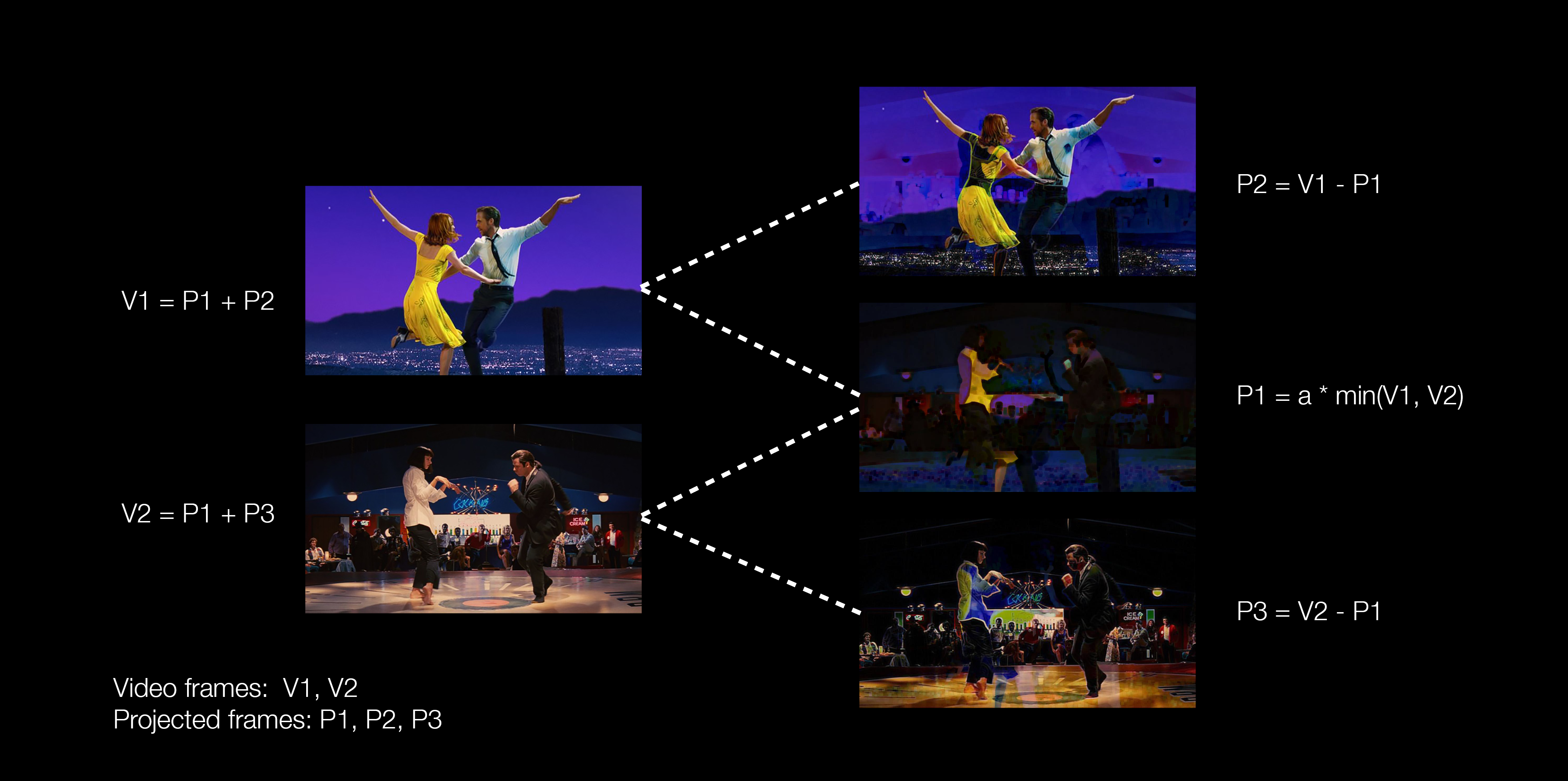

In this installation, the participants challenge the assumption that shadows and images are opposite by revealing images through cast shadows of their bodies. Three projectors are installed about 12 feet from the screen in varying orientations and are calibrated to overlap. Each projection shows a decomposed part of two videos. Only the combination of two overlapping projections, instead of one or three, shows a valid frame. When the participants block one projector with their bodies, the valid frame is revealed within their cast shadows. Participants’ bodies are thus integrated into the image display pipeline as shadows.

In this installation, the participants challenge the assumption that shadows and images are opposite by revealing images through cast shadows of their bodies. Three projectors are installed about 12 feet from the screen in varying orientations and are calibrated to overlap. Each projection shows a decomposed part of two videos. Only the combination of two overlapping projections, instead of one or three, shows a valid frame. When the participants block one projector with their bodies, the valid frame is revealed within their cast shadows. Participants’ bodies are thus integrated into the image display pipeline as shadows.

we’ll meet where there is no shadow, interactive installation, 2024

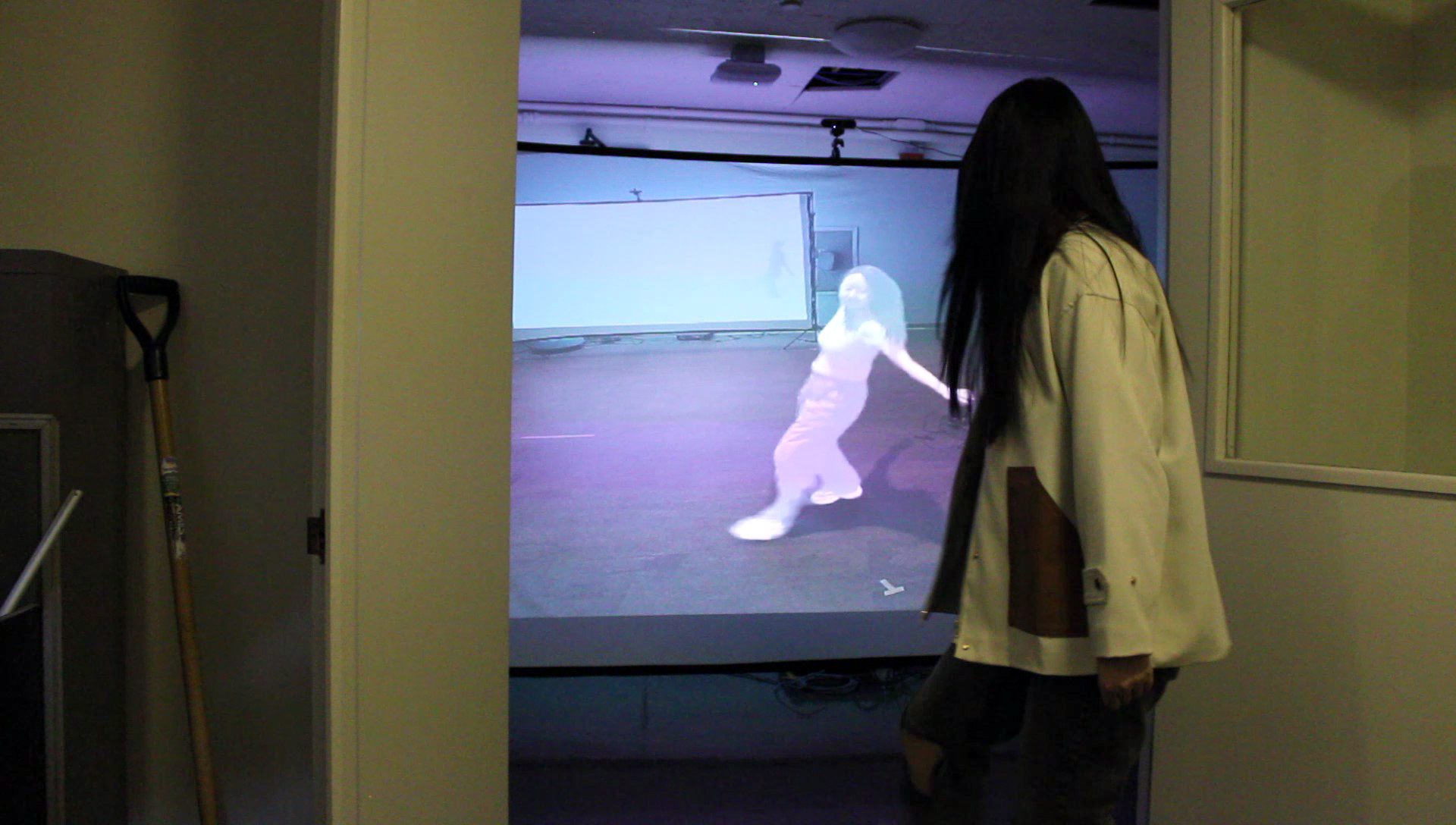

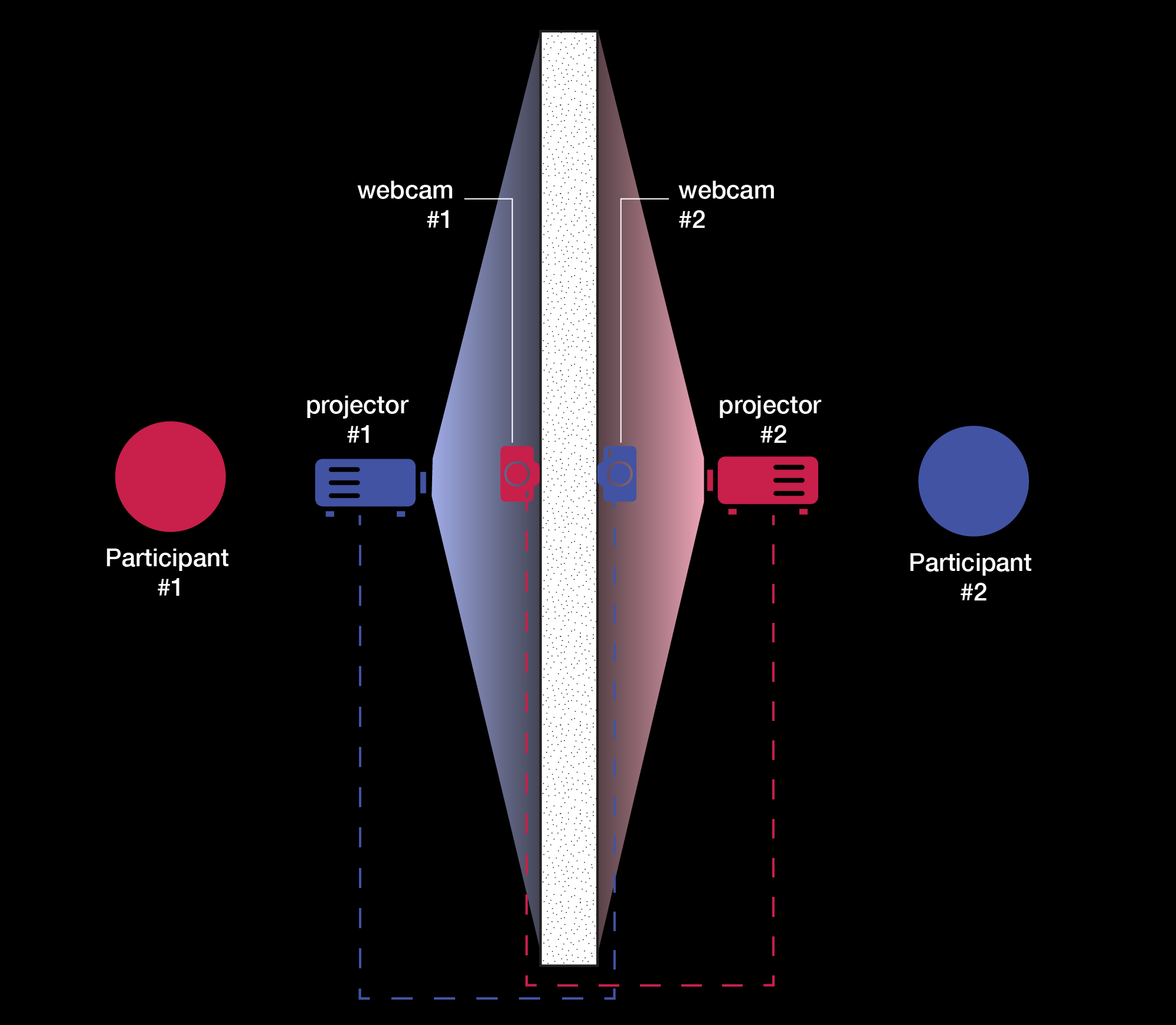

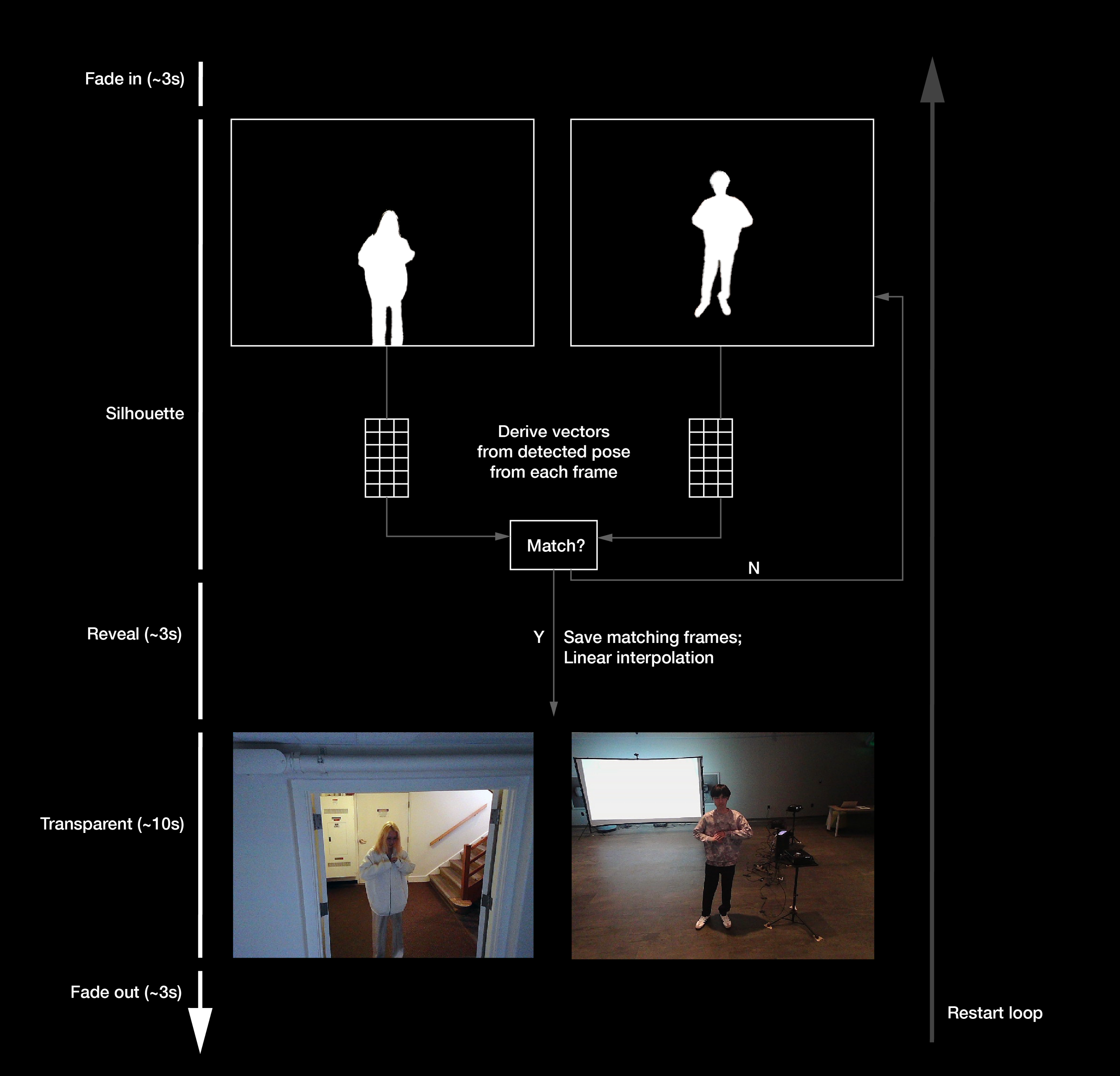

This installation sets up a playful and collaborative imaging pipeline between two participants that consists of a challenge and a reward. For the challenge, the participants are divided by a solid wall, and they can only see their partner’s silhouette. Without verbally communicating or seeing themselves, they need to match the shadow’s poses by attempting to inhabit each other’s bodies. For the reward, after matching, the participants see each other and the room behind the wall, as if the solid wall between them turns transparent. In this pipeline, meaningful and affective connections form not only between bodies and images but also between multiple bodies and the physical space they share.

This installation sets up a playful and collaborative imaging pipeline between two participants that consists of a challenge and a reward. For the challenge, the participants are divided by a solid wall, and they can only see their partner’s silhouette. Without verbally communicating or seeing themselves, they need to match the shadow’s poses by attempting to inhabit each other’s bodies. For the reward, after matching, the participants see each other and the room behind the wall, as if the solid wall between them turns transparent. In this pipeline, meaningful and affective connections form not only between bodies and images but also between multiple bodies and the physical space they share.

Technical Details

Exhibition:

Data Experiences and Visualizations Studio, Dartmouth College

April 2024

Medium, Device and Technology:

Optoma ZH420UST, Viewsonic PJD7820HD, two-sided projection screens, EMEET SmartCam C960, computers, MediaPipe Pose

Tags:

interactive installation, computer vision, computational imaging, embodiment, alternative imaging and display technologies

Data Experiences and Visualizations Studio, Dartmouth College

April 2024

Medium, Device and Technology:

Optoma ZH420UST, Viewsonic PJD7820HD, two-sided projection screens, EMEET SmartCam C960, computers, MediaPipe Pose

Tags:

interactive installation, computer vision, computational imaging, embodiment, alternative imaging and display technologies

Publications:

SIGGRAPH Asia 2024 Art Paper

Yunzi Shi, John Bell, and Adithya Pediredla. 2024. Embodied Visions: Interactive Installations That Reimagine Bodily Presence in Digital Imaging Apparatuses as Shadows. In SIGGRAPH Asia 2024 Art Papers (SA '24). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 8, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1145/3680530.3695436

Thesis Shi, Yunzi, "Embodied Visions: Interactive Installations That Reimagine Bodily Presence in Digital Imaging Apparatuses as Shadows" (2024). Dartmouth College Master’s Theses. 153.

https://digitalcommons.dartmouth.edu/masters_theses/153

SIGGRAPH Asia 2024 Art Paper

Yunzi Shi, John Bell, and Adithya Pediredla. 2024. Embodied Visions: Interactive Installations That Reimagine Bodily Presence in Digital Imaging Apparatuses as Shadows. In SIGGRAPH Asia 2024 Art Papers (SA '24). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 8, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1145/3680530.3695436

Thesis Shi, Yunzi, "Embodied Visions: Interactive Installations That Reimagine Bodily Presence in Digital Imaging Apparatuses as Shadows" (2024). Dartmouth College Master’s Theses. 153.

https://digitalcommons.dartmouth.edu/masters_theses/153

Acknolwedgement:

Lorie Loeb

Quinton (Ziyuan) Qu

labmates, visitors and interview participants

Data Experiences and Visualizations Studio, DartmouthRendering and Imaging Science Lab, Dartmouth

Jones Media Center, Dartmouth

Lorie Loeb

Quinton (Ziyuan) Qu

labmates, visitors and interview participants

Data Experiences and Visualizations Studio, DartmouthRendering and Imaging Science Lab, Dartmouth

Jones Media Center, Dartmouth